Fibre is one of those nutrients you hear a lot about, yet many people don’t really know what it is and why it’s so important. I promise, fibre is not just for your grandmother with her prune juice. It’s a super important component of our diets and can do wonders for your health. Let’s break it down.

What is fibre?

Fibre is mostly made of carbohydrates and other similar substances that are not completely digested by our bodies. Because it is not digested and absorbed, fibre moves from the small intestine to the large intestine (also called the colon), and some of it gets fermented there by our resident gut bacteria, while the rest comes out in our stool.

Fibre can be characterized many different ways based on its structure and other characteristics, but the most widely accepted distinctions are between soluble and insoluble fibre, and between dietary and functional fibre.

Soluble fibre vs. Insoluble fibre

Classifying fibre by its solubility (whether it can dissolve in water) is useful because if a fibre is soluble, it has slightly different physiological effects. Soluble fibre is a type of fibre that can dissolve in water, and because of this property, it becomes a viscous gel-like substance inside our digestive system. This is helpful because it allows soluble fibre to bind substances like cholesterol and prevent them from being absorbed. This is why eating foods high in soluble fibre can help lower cholesterol levels. Insoluble fibre, on the other hand, does not dissolve in water but rather adds bulk and helps keep you regular. Keep in mind that many foods contain both types of fibre, and within each of these categories there is a wide range of complex molecules, each with its own unique characteristics.

Dietary fibre vs. functional fibre

This is the second way to define fibre, this time by its benefits to human health. While dietary fibre is defined as non-digestible carbohydrates and lignin (complex molecules present in plants), functional fibre is defined as non-digestible carbohydrates that have beneficial physiological effects in humans. So here, the main distinction has to do with whether the fibre is known to have important health effects, aside from the usual health benefits of all fibre types.

A word on resistant starch

Resistant starch is a type of insoluble fibre that has recently come to light as potentially beneficial to human health. Starch is a type of carbohydrate made up of many glucose molecules chained together. It is used by plants to store energy, and usually gets broken down when we eat these plants. But some types of starch can resist digestion, and this is important because this resistant starch makes it into our colon and makes for the perfect meal for our gut bacteria. This is why resistant starch is defined as a prebiotic – it feeds our gut microbiota and allows them to grow. Apparently, this can help us feel full too, which is an interesting and not completely understood phenomena. Lastly, resistant starch has been found to reduce our glycemic response (spike in blood sugar after eating), so it can be useful for managing diabetes.

How much fibre should you eat?

Most recommendations for fibre intakes are for all fibre types put together. The Institute of Medicine recommends an intake of 14 grams of fibre per 1000 calories of energy, which translates roughly to 25 grams per day for women and 38 grams per day for men.

Sources of fibre

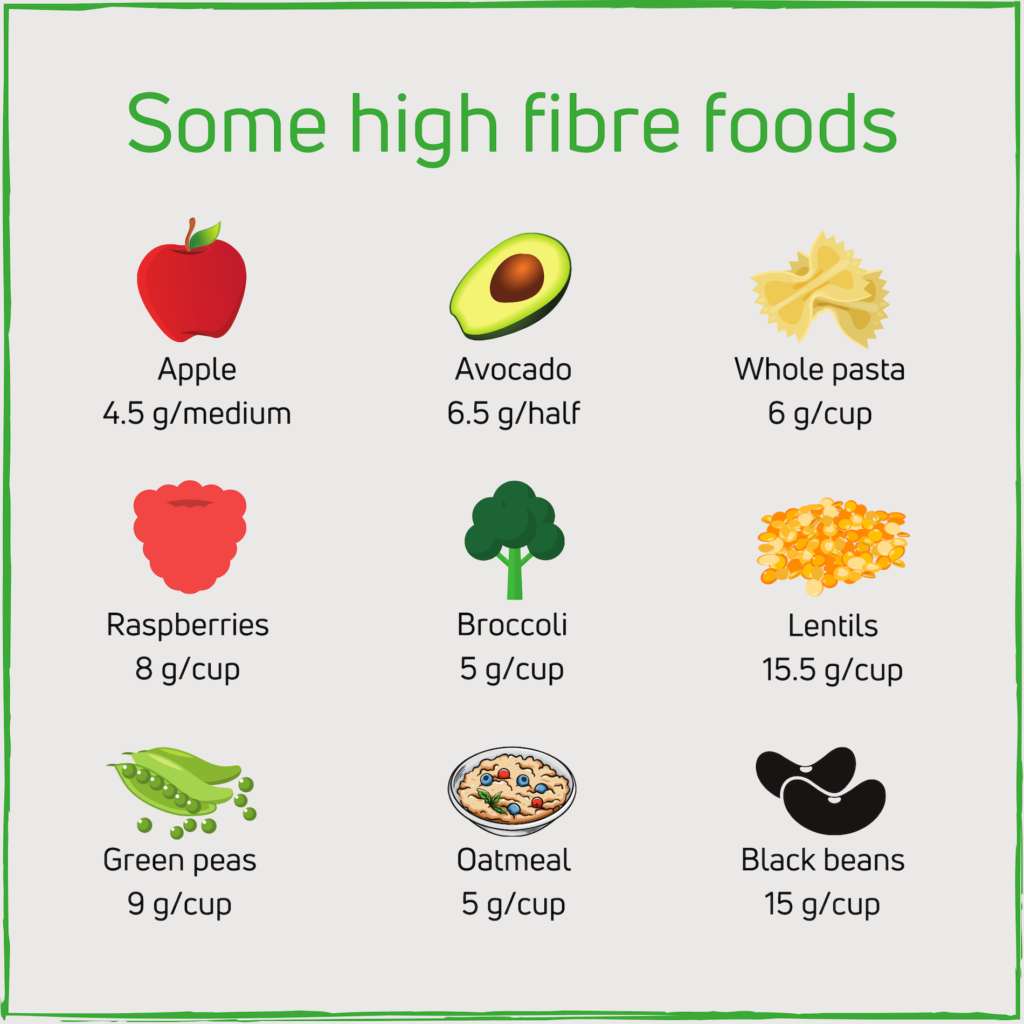

Good sources of fibre include fruits and vegetables, whole grains, nuts and legumes. If we want to break it down by fibre type, you can find soluble fibre in foods like oats, beans, apples, and psyllium. Psyllium husk specifically can be found in most health food stores and used as a fibre supplement (similar to Metamucil). Insoluble fibre can be found in grains, fruits, and nuts. Wheat bran is a good source of insoluble fibre.

If you’re specifically interested in resistant starch, it is found in legumes, plantains, oats, and cooked and cooled potatoes and rice. Some resistant starch breaks down in cooking, which is why eating uncooked oats will give you more resistant starch than eating cooked oats. One nice way to add more resistant starch to your diet is by having overnight oats.

Health benefits of fibre

As mentioned above, each fibre type has specific properties and may bring with it specific health benefits. In this section, I’d like to address the health benefits of all fibre types put together. Most Canadians and Americans eat about half of the recommended daily intake of fibre, so increasing fibre intake is important no matter what type it is. At the end of the day, increasing your fibre intake from any source will be beneficial. Here’s why:

Laxation and constipation

This topic may be a bit private, but let’s just say constipation is a very common issue. Increasing fibre intake can help make you more regular. But beware, taking in too much fibre at once will have the opposite effect. So the best thing to do if you want to address constipation is to slowly increase your fibre intake while also increasing your water intake. This will make sure there is enough fluid and bulk to move things along.

Cardiovascular disease

The recommendations above set by the Institute of Medicine are actually based on cardiovascular disease prevention. Getting your recommended daily intake of fibre will help lower bad cholesterol, which reduces the risk of heart disease. Some studies also show a reduction in blood pressure with increased fibre intake. It seems that when it comes to cholesterol, soluble fibre does a better job of lowering LDL (bad cholesterol), which is why in the United States, some products such as oats, barley, and psyllium, are allowed to advertise that they lower cholesterol. At the end of the day, adding a variety of fibre-containing foods to your diet can help prevent heart disease.

Glycemic control and type 2 diabetes

There seems to be a strong relationship linking fibre intake and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. This could be because of fibre’s role in lowering glucose absorption in the gut, as well as the fact that many fibre-containing foods are also rich in other beneficial nutrients. In general, having high-fibre foods will help with glycemic control.

Appetite

Having high-fibre foods can help keep you full longer, which is helpful if you’re trying to lose weight. Turns out this association may be caused by many factors, including the fact that fibre-containing foods take longer to chew, absorb water and cause stomach distention (they expand the stomach), and take longer to pass through the stomach.

Cancer

It is currently unclear whether fibre intake is protective against colon cancer, but there is some evidence to suggest this may be the case. In general, a diet that is high in fibre is also high in many other protective nutrients, which is why this association may exist.

Gut microbiota

What we eat affects the amount and type of our gut bacteria. We have many different types of gut bacteria, all with unique effects on our health, which makes the impact of food on health even more difficult to assess. In general, because diets rich in plant-based foods provide many fibre types, they support more diversity in our gut bacteria. Fibre types that get fermented in the gut are considered “prebiotic” because they feed our gut bacteria. These bacteria in turn make short-chain fatty acids, essentially fat molecules, that feed OUR colon cells. So having happy gut bacteria also makes for a healthier gut. There is also some research that suggests other health benefits like reduced inflammation, cholesterol, and blood glucose, but this type of research is still brand new and these links are not completely formed.

Some fibre-rich recipes:

The bottom line

Fibre is good for you. Most people don’t get enough fibre, so adding fibre-containing foods to your diet is usually a good idea. Try to add a variety of foods, including fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts. This will ensure you also get all of the other important nutrients inside these foods. And lastly, if you are currently eating very little of these foods, add them in slowly and make sure to hydrate.

References

- Health Canada. (2019). Fibre. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/nutrients/fibre.html.

- Holscher, H. D. (2017). Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes, 8(2), 172-184. DOI: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756.

- Johns Hopkins University. (2020). What is resistant starch? Retrieved from https://hopkinsdiabetesinfo.org/what-is-resistant-starch/.

- Lockyer, S. & Nugent, A. P. (2017). Health effects of resistant starch. British Nutrition Foundation Nutrition Bulletin, 42, 10-41. DOI: 10.1111/nbu.12244.

- Mérillon, J. M. & Ramawat, K. G. (eds.). Bioactive Molecules in Food, Reference Series in Phytochemistry. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78030-6_7.

- Willis, H. J., & Slavin, J. L. (2012). Dietary Fiber. In A. C. Ross (Ed.), Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease (58-64). Wolters Kluwer Health.